Ghana’s poultry industry is in deep distress as a growing glut of unsold eggs forces farmers to slash prices, cut production and contemplate shutting down operations altogether. Producers in the Greater Accra region say more than 38,000 crates of eggs are currently sitting on farms without buyers, a situation they describe as unprecedented and potentially ruinous.

Farmers trace the crisis to a combination of factors. They argue that large, well-resourced producers — including foreign-owned operations — have expanded aggressively in recent years, boosting output far beyond what the local market can absorb. At the same time, they accuse some retailers of keeping their prices high even as the farm-gate price of a crate has fallen to between GH¢40 and GH¢45. With consumers unwilling to buy at inflated retail prices, eggs are piling up in storage. The absence of a cold-chain system or adequate processing capacity means that unsold stock begins to spoil within days, deepening losses.

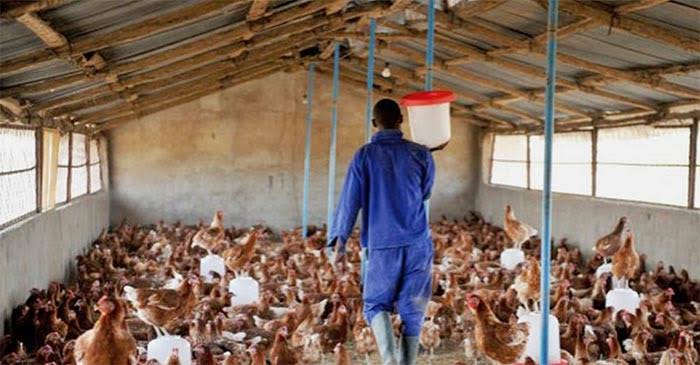

For many farm owners, the financial strain is becoming unbearable. Feed costs remain high and workers must still be paid even when nothing sells. One farm owner producing about 30 crates a day said she cannot meet basic expenses and fears she may soon have to shut down. Some workers have already reported delays in their wages and uncertainty about how long they will remain employed. Industry groups warn that at least a dozen farms have either collapsed or scaled back significantly in recent months.

The crisis has led to loud calls for immediate government intervention. Farmers want pricing policies that protect farm-gate income, guaranteed purchases by state institutions and clearer enforcement of directives requiring schools and government agencies to buy local agricultural products. They also want tighter oversight of foreign-owned poultry enterprises, arguing that unregulated expansion is crowding out local producers and destabilising the market.

Economists say the situation exposes deeper structural weaknesses in Ghana’s poultry value chain. With no coordinated system to match production to demand, no national programme to absorb surpluses and limited value-addition capacity, farmers remain vulnerable to sudden market shocks. Without swift action, analysts fear that the effects will spread beyond laying farms to hatcheries, feed producers, transporters and other supporting businesses.

It remains to be seen what can be done to resolve the problem but the longer eggs remain unsold, the more farmers lose, and once they begin culling birds or winding down production, the recovery process could take months. Many fear that if the crisis is not addressed urgently, Ghana could witness the collapse of an industry that has long been seen as a vital source of jobs, food security and rural livelihoods.