Dr (Mrs) Nana Konadu Agyeman-Rawlings, former First Lady, was one of Ghana’s most influential champions of women’s rights and political participation.

Born on 17 November 1948, Nana Konadu’s life spanned Ghana’s late colonial years, independence, military coups and the return to constitutional rule. Across those decades she carved out a distinct identity: an activist First Lady, a driving force behind landmark women and children’s legislation, and later a party leader and presidential candidate in her own right.

She was born into privilege and duty. The third of seven children, she was the daughter of John Osei Tutu Agyeman (widely known as JOT) and Felicia Agyeman (née Sarpong), a daughter of a wealthy Ashanti merchant from Mpobi in the Ashanti Region. Her paternal grandfather, Oheneba Owusu Sekyere Agyeman, was a son of the 11th Asantehene, Otumfuo Mensah Bonsu. She was named for her grandmother, Nana Konadu Yiadom III, the 11th Asantehemaa.

Her mother, an educationist, was barred by colonial law from teaching after marriage, but turned her skills inward, drilling her children in mathematics, English and elocution at home. Her father rose to become the top Ghanaian manager of the United Africa Company in the Gold Coast and was known for hard work and integrity. Their home was disciplined and socially active, shaped by Ashanti traditions of protocol, good manners, self-reliance and a strong sense of responsibility.

The Agyemans valued education and moved their children through some of the country’s best schools. Young Konadu’s early years were steeped in both formal learning and informal political education. As nationalist sentiment intensified, debates about independence and colonial injustice were common in the family home. She later recalled that her mother and other married women were “rendered virtually powerless” by British law, even as the broader fight against colonial rule took centre stage. Those early exposures to both oppression and gender inequality helped form the convictions that would define her public life.

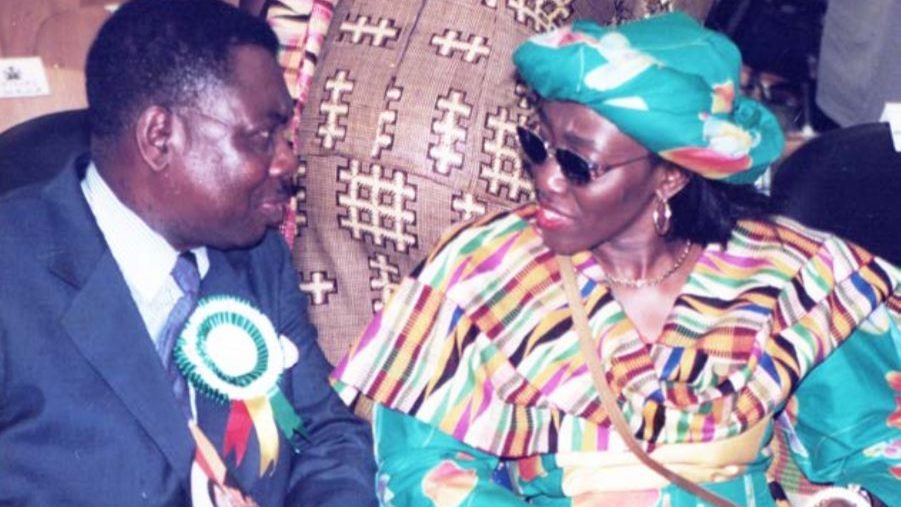

She first met a boy called Jerry John at Progress School, commonly known as Mrs Sam’s School, in Accra. After two years there she moved to Ghana International School, where she made life-long friends, and then to Achimota School in 1961. Achimota deepened her sense of public duty and expanded her circle of future national influencers. It was also where she crossed paths again with that same boy from Mrs Sam’s. He was now a classmate, bright and restless, and would later become her husband and Ghana’s head of state, Flight Lieutenant Jerry John Rawlings.

By her own account, their relationship did not begin smoothly. She once recalled disliking him so intensely that she reported his behaviour to the headmaster. Yet he kept turning up, including at Protestant choir practice, despite being Catholic. She would only later discover that he had joined the choir simply to be near her.

At Achimota she witnessed history at close range. As a teenager in Kingsley House she woke up one morning in 1966 to commotion in the dormitory and news on the radio that President Kwame Nkrumah had been overthrown. She watched as Nkrumah’s books were burned on campus, an act she recalled with shock.

After completing her O-levels at Achimota, she stayed for A-levels, while Jerry Rawlings left to pursue his dream of becoming an air force pilot. He enlisted as a flight cadet in 1967 and went on to win the Speed Bird Trophy. She moved to the University of Science and Technology, now KNUST, to study Graphic Design and Applied Arts. On campus, her political consciousness sharpened. The economic downturn of the early 1970s, widespread hardship and what she saw as entrenched corruption pushed her into student activism.

In 1969 she ran successfully for the Students Representative Council and became SRC secretary. She helped organise demonstrations against corruption and inefficiency on campus and served on the National Union of Ghana Students, working with peers from across the country who shared similar aspirations. She graduated with honours in 1972, just as another coup toppled the government of Prime Minister Kofi Busia.

After university, she joined the Ghana Tourist Board and later Union Trading Company (UTC), then one of Ghana’s largest trading firms, rising to Group Manager. In 1975 she earned a diploma in interior decoration from the London College of Arts. These early professional years, which included design work in gated executive compounds around the country, exposed her to stark inequalities between the lifestyles of corporate and expatriate elites and the poverty of rural women beyond the compound walls. That contrast left, in her words, “an indelible mark” on her mind and helped channel her activism towards women and children.

On 29 January 1977 she married Jerry John Rawlings at Ridge Church in Accra. He was then a young officer in the Ghana Air Force. Their first daughter, Zanetor, was born in June 1978 during severe economic decline. Her Ewe name, meaning “let the darkness end,” reflected the mood of the period.

Rawlings would go on to lead the June 4 uprising in 1979 and later return on 31 December 1981 to head the Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC). With that second intervention, Nana Konadu formally entered national life as First Lady. She chose not to treat the role as ceremonial. Instead, she set out to build a women’s movement that could influence policy and change lives at the grassroots.

In 1983 she and a group of like-minded women founded the 31st December Women’s Movement, with the goal of empowering women socially, economically, culturally and politically. Over time the movement grew to almost two million members across Ghana, drawing in women of all backgrounds and organising educational programmes, workshops, theatre projects and income-generating ventures in tie-dye, shea butter, palm oil, gari processing, basket weaving and small-scale farming.

Working often with limited resources, she frequently used her own funds to sustain projects. She also secured support from UN agencies and other international partners. Under her leadership, the movement helped to establish more than a thousand early childhood centres, rolled out family-planning education in hundreds of communities, drilled boreholes in Guinea worm-endemic areas, launched afforestation schemes in northern Ghana and even planted trees along major urban corridors such as Independence Avenue and the Tema Motorway.

In health, she partnered with the Ministry of Health on prenatal, postnatal and child immunisation programmes and worked with Nelson Mandela on the “Kick Polio out of Africa” campaign in 1996. She later championed the construction of radiotherapy centres at Korle Bu, Komfo Anokye and Tamale Teaching Hospitals, raising funds from China, the United States and the International Atomic Energy Agency. She was also involved in securing mobile hospital units and loans for large projects, including a cocoa processing factory and career training institutions in Kanda and Dansoman.

Her advocacy was central to a series of legal reforms under the PNDC that strengthened protections for women and children. Key among them was the Intestate Succession Law, PNDC Law 111, which for the first time guaranteed a surviving spouse and children a share of the estate when a man died without a will. That law has since shielded countless widows from customary practices that stripped them of their homes and livelihoods. She consistently credited pioneers such as Justice Annie Jiagge and other Ghanaian women for shaping the agenda that informed these laws.

As First Lady, she also invested heavily in children’s education and cultural grounding. She created the television programme “By the Fireside” on GTV, which used storytelling, song and dance to revive folklore and pass on moral lessons. Later, “Story Time” focused on diction, reading and writing skills for younger viewers.

Alongside her activism she continued to study, taking diplomas at the Management Development and Productivity Institute and the Ghana Institute of Management and Public Administration in areas such as human resource management, administration and population. She later became a Senior Fellow at Johns Hopkins University, where she pursued policy studies, and in 1995 received an honorary doctorate in social science from Lincoln University. She was recognised as a Fellow of the West African College of Nursing and served on the World Health Organisation’s Global Commission on Women’s Health.

On the global stage, she was a prominent voice at conferences on women, population and development, peace and health. At the 1995 Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing, she spoke powerfully about the African girl child, insisting that girls must receive “education that empowers, education that gives skills, and education that builds self-confidence.” Ghana had by then become the first country to ratify the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, a step she had strongly championed.

She was outspoken against child marriage and worked to support the eventual setting of the minimum age of marriage at 18. “We refuse to accept girl children as mothers at this tender age,” she said, arguing that they belonged in school, preparing for independent adulthood and leadership.

With the transition to multiparty democracy, she played a key role in the formation of the National Democratic Congress. While some PNDC members returned to their old parties, she argued for a new organisation that embodied the ideals of probity, accountability and social justice. She helped conceptualise and design the NDC’s emblem and led extensive grassroots mobilisation for the 1992 elections, which returned Rawlings as the first president of the Fourth Republic.

After 1993 she continued her dual work as First Lady and president of the 31st December Women’s Movement, maintaining a clear distinction between the two roles. She travelled with the president on official visits to promote investment and trade and used those trips to solicit support for community projects. She also built regional and international networks, including with other African First Ladies, and hosted peace and humanitarian conferences in Accra.

Her political engagement did not end when Rawlings left office in 2001. She remained an influential figure within the NDC, supporting candidates, defending the party’s record in the media and helping to build its youth and campus structures. In 2009 she was elected first vice chairperson of the party. Two years later she made history as the first woman to challenge a sitting Ghanaian president for the NDC flagbearership, contesting John Evans Atta Mills at the Sunyani congress.

After that defeat, she left the NDC and founded the National Democratic Party in 2012, becoming its presidential candidate in the 2016 elections. The move was controversial, but for her it was in line with what she described as a lifelong commitment to probity, accountability and staying true to her convictions.

Beyond politics, she continued to mentor women across party lines, campaigning for female parliamentary candidates and urging younger activists to take up public service. She received numerous awards over the years, including the Woman for Peace Award in Rome in 1994, the Drum Major for Justice Award in Atlanta in 1997 and top honours from Soka Women’s College in Japan. She treated them less as personal accolades than as platforms to highlight the struggle for equality and justice.

She also wrote and published widely. Among her works are “The Japanese Co-operation with the 31st December Women’s Movement,” “The Development of Ghanaian Women’s Attire from 1700–1900” and “Effective Design Work and Interior Design.” Her memoir, “It Takes A Woman,” was published in 2018, followed in 2025 by “For Hope and Country,” which reflected on her life, Ghana’s political journey and the burdens and privileges of leadership.

Looking back on her journey, she once wrote: “My family’s heritage had carried a weight of its own, and I knew I was fortunate to have rested on the shoulders of these courageous men and magnificent women to now make my little contribution. I had to embrace it as God’s purpose for my life and determine to never falter in that commitment. That was not the life I chose; it chose me.”

Dr (Mrs) Nana Konadu Agyeman-Rawlings was the third of seven children of the late J.O.T. Agyeman, a statesman, and the late Felicia Agyeman, an educationist. She was the wife of the late Flt Lt Jerry John Rawlings, former President of the Republic of Ghana. She is survived by four children, Hon. Zanetor Agyeman-Rawlings, Member of Parliament for Klottey Korle, Yaa Asantewaa Agyeman-Rawlings, Amina Agyeman-Rawlings and Kimathi Agyeman-Rawlings, and six grandchildren. Her influence endures in the laws she helped shape, the institutions she built and the generations of women and girls who found in her life story a reason to believe that they, too, could lead.